By Maaya Prasad

Many who read this blog might wonder how life on a research vessel is like. I had never been on a moving ship overnight, so naturally, I expected to be able to feel the boat’s every motion after we left port. The day we launched, Noa and I had ventured into the galley, imagining a picturesque departure where we would watch Cape Cod fade into the horizon while sipping a warm mug of coffee. In reality, the coffee machine was slow and we were impatient, so when we left the still-brewing pot to check on our departure status, we were both shocked to see that we had departed ten minutes ago, and neither of us had felt it (Cape Cod was already in the distance, and we had no coffee in hand to celebrate!).

Although we mostly had calm seas throughout the cruise, the experience could often be how I previously imagined it—hallways tilting like a fun house and gravity seemingly transforming from constant to variable as the ship rolled across the waves. In the gym (which could be found after climbing down a hatch), Noa and I discovered that part of the challenge of weightlifting on a rocking vessel meant anticipating the weight growing suddenly heavier or lighter. During a Pirates of the Caribbean movie night, a particularly sudden roll sent me and my cup of tea stumbling across the room just as a pirate pitched overboard onscreen (definitely a 4D experience!).

However, we soon adjusted to the staggering pace of life adopted on a research vessel at sea. The days were quite busy, with each team juggling a myriad of tasks and science objectives, each of which was reflected in the two dozen monitors peppered around the room. Salinity charts, CTD graphs, navigation maps, and vehicle tracking interfaces could all be seen with one glance. While our jumble of thoughts lived mostly within the screens, they would occasionally spill across the tables in the form of miscellaneous vehicle parts, colorful images, and VMP components. The lively atmosphere crackled with radio messages, Glen’s energetic announcements about our latest scientific discoveries, and at least one AUV operator yelling to another outside, “We got a range!”

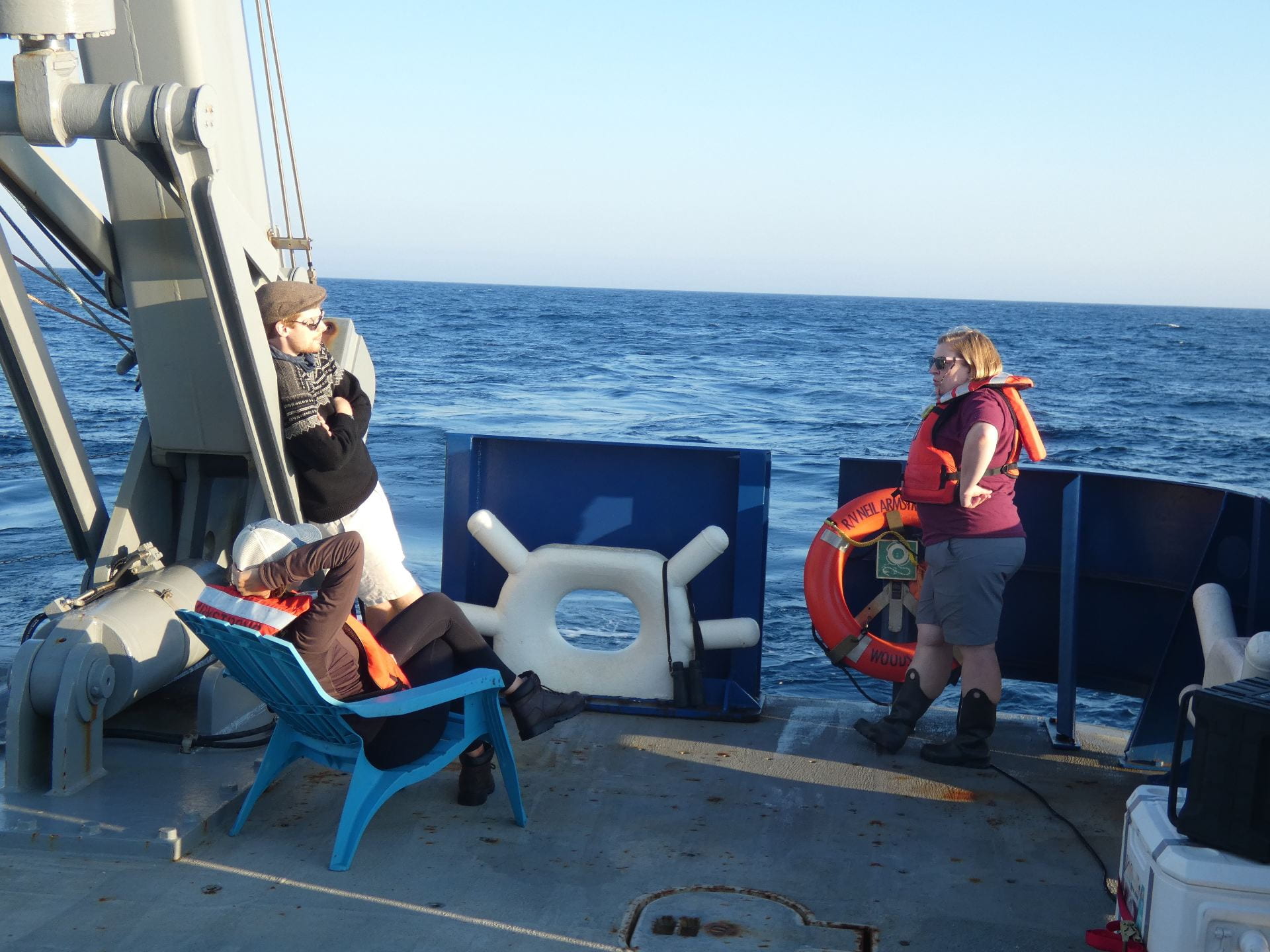

Thankfully, throughout the continuous operations, we were each able to find small moments to unwind and enjoy our time offshore. For example, when I asked Lukas one afternoon how his VMP shift had gone, he described a tranquil experience relaxing in a lounge chair on deck while eating a small plate of cheese and crackers and supervising the VMP. “It’s almost like being on a real cruise ship,” he told me.

Despite the long days, working on the ocean was refreshing after a year of virtual work. The ocean’s moods were turbulent, changing from day to day. Sometimes the horizon remained mysterious, shrouded behind layers of mist and mantles of fog, while other times the dancing waves seemed as playful as the dolphins leaping through them. Each sunset cast gossamer films of gold across the water, followed by the iridescent shades of a moonrise. At night, the ocean merged into the sky and transformed into a yawning abyss, dimly illuminated by the Milky Way and occasional lightning bottled in distant thunderstorms. The water swallowed most light—even the bright ship lights we used when searching for squid brightened only a small turquoise patch (just enough to see squid flash by like quicksilver) before fading into ominous black waves.

After two weeks on a research vessel, I can’t deny that I’m more than a little exhausted—and I’m sure I’m not alone in these sentiments. But the energy supplied by our enthusiastic crew made the long sixteen-hour days fly by. Our team bonded over more than just the incredible science we were accomplishing—we chattered over EuroCup matches, shared movie nights and book discussions, and jigged for squid late into the night. When we reach land, I won’t only miss working on the waves, but also working with the amazing and dedicated crew aboard the AR58 cruise.